Fin Whale Fast Facts

Scientific name: Balaenoptera physalus

Class: Mammalia

Average length: 60 to 70 feet

Average weight: 40 to 80 tons. Calves weigh about 4,000 to 6,000 pounds at birth.

Average lifespan: Estimated at around 80 to 90 years

Current population: About 3,200 off of California, Oregon, and Washington. Between 14,000 and 18,000 are estimated for the entire North Pacific. In the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, the population is about 2,700 fin whales and the southern hemisphere has around 82,000.

Gestation period: 11 to 12 months

Fin Whale

Fin Whales: Dive Deeper

In Dana Point, California, over six species of whales are spotted. From blue whales, gray whales, minke whales, fin whales, and humpback whales, these whales are what make our city the whale watching capital of the world®. With a handful of remarkable and massive giants roaming the open ocean, one leaves us breathless with its magnificent and sleek self. This particular species of whale is known as the ‘fintastic’ fin whale. Sometimes called the finback whale, and scientifically known as Balaenoptera physalus, this incredible marine mammal visits the waters off Dana Point year-round and captivates us with its variety of unique characteristics and features.

The fin whale is the second-largest baleen whale, following its close and colossal relative, the blue whale. Measuring in at 70 to 80 feet long, with females being slightly larger than males, these whales have an amazing appearance that sets them apart from other swimmers out at sea. Fin whales have an estimated lifespan of 80 to 90 years.

What do Fin Whales Look Like?

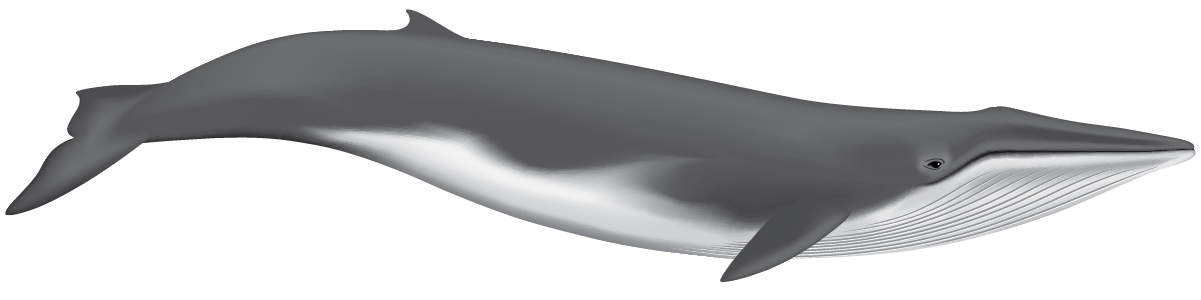

The fin whale is generally light gray to brownish-black on its back and sides. It has a long, sleek, and streamlined body that begins with a large V-shaped head. Under its lower jaw, it has unique asymmetrical coloring, with gray or black on the left side and white on the right side. The fin whales grayish colored body begins to lighten where two v-shaped “chevrons” rest midline behind their large blowhole and above their tall, curved dorsal fin.

This dorsal fin resembles a hook and sits about two-thirds of the way down its body, giving them their famous “fin” whale name. The underside belly area of this enormous creature is white, including its flippers and fluke. The white coloring on the tail flukes is often bordered with a distinct gray shade, making each and every fin whale different from the next. Each marking is unique and enables researchers and scientists to identify each individual whale. The beautiful asymmetrical and gray colored bodies of these fin whales mark the scales at up to 80 tons, equivalent to the weight of nearly seven school buses.

What Do Fin Whales Eat?

Fin whales maintain a stealthy weight by consuming up to two tons of food a day. This food consists of krill, a small crustacean, as well as small schooling fish such as capelin, herring, and sand lance. An additional menu pick can also include a scrumptious choice of squid.

When seeking prey, the fin whale has been observed as they circle schools of fish. This circling is done at high speeds, where the fin whale rolls the schools of fish into compact balls and then turns on its side to engulf the grub in its large mouth. Because the fin whale is a rorqual whale, it has a series of 100 – 200 throat grooves that expand like an accordion when catching their prey. As they snatch up the fish in their large jaw area, these grooves expand to fit a large amount of both fish and seawater. With the aid of their 250 to nearly 500 baleen plates, the fin whale filters the food particles as the saltwater strains from their massive mouths. Their feeding grounds are found in the Arctic and Antarctic, various parts of North America and in the nutrient dense waters of Dana Point.

Where are fin whales found?

In addition to their feeding grounds, fin whales reside in deep offshore waters in all of the earth’s major oceans, most especially in temperate to polar latitudes, and less so in the tropics. Although hanging about in a large variety of locations, their whereabouts change seasonally.

Traveling in the open ocean, away from the coast, this particular species of whales can be challenging to track as they are a migratory mammal, moving seasonally in and out of feeding areas. Although somewhat difficult to keep tabs on, three different subspecies have been discovered including B. physalus physalus in the northern hemisphere in North Atlantic and North Pacific, B. physalus quoyi in the southern hemisphere of the Southern Ocean, and B. physalus patachonica in the mid-latitude Southern Ocean. Most groups, which are made up of social clusters of two to seven individuals, migrate from their feeding grounds in the Arctic and Antarctic to their breeding grounds in tropical areas during the winter months.

Scientists from NOAA Fisheries, Ocean Associates Inc., Cascadia Research Collective, Tethys Research Institute, and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, have recently identified fin whales in the northern Pacific Ocean as a separate subspecies: Balaenoptera physalus velifera.

According to their report published in August 2019 in the Journal of Mammology, using DNA from tissue samples of fin whales obtained in the field, and comparing the DNA from whales in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, has shown that the species have been separated for hundreds of thousands of years. Using the genetic data, they could also assign individual samples to their ocean of origin, which provides even more evidence that they’re separate subspecies.

Unlike other large whales, fin whales rarely raise their tail flukes in the air and almost never jump out of the water (breaching). Every once in a while though, and always immediately after the Captain says “fin whales never breach”…

Fin Whale Mating and Calves

In regards to breeding, fin whales become sexually mature between the ages of 6 and 12 years old with males reaching sexual maturity between the ages of 6 and 10 and females between 7 and 12. After reaching maturity, female fin whales carry a single calf during a 12 month gestation period and give birth in tropical and subtropical areas during midwinter. A newborn calf weighs between 4,000 to 6,000 pounds and stretches to lengths of 18 feet long. They and their species can live to a mature age of up to eighty years.

Although some are known about the breeding and birthing grounds of this species, little is known about their social and mating patterns. Whether this is due to their migratory habits, or the fact that as with other baleen whales they do not often form long-term bonds between one another, we are uncertain. Fortunately, in regards to social communication, scientists have discovered that they have a unique way of communicating, and like other large baleen whales, they use a series of grunts, groans, pulses, and moans to communicate with others fin whales. This unique chatter can travel and be heard from long distances away from where the sound is originally produced. Regardless of how little or how much is known about their social and mating patterns, they are an extraordinary creature bringing joy to the oceans they call home.

Is the Fin Whale Endangered?

While bringing joy and ebullience to the vast and diverse ecosystem out at sea, fin whales face many threats and challenges to their well-being and survival. In the mid-1900s, 725,000 fin whales in the southern hemisphere alone were killed by commercial whalers. Between 1947 and 1987 whalers killed about 46,000 fin whales in the North Pacific. Gratefully, between the years 1970 and 1980, commercial whaling was discontinued, making the devastating practice of whaling no longer a threat to these incredible giants. Although whaling is no longer a major threat to this species, some hunting does exist in Greenland with whaling subsistence from the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

The biggest threat that currently faces the fin whale population comes from vessel strikes. Other threats include ocean noise that causes the whales to strand and ultimately die. In addition, entanglement in fishing gear is also a threat to fin whales, as they can often become entangled in different gears such as pots, gillnets, and traps. Once entangled, the whales can swim while dragging the attached gear for long distances, ensuing in compromised feeding, fatigue, severe injury leading to problems with reproduction, and sadly, even death.

With So Many Threats, One May Ask, “How Many Fin Whales Are Left?”

Although listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, there are nearly 100,000 fin whales cruising the deep blue today. These numbers include both the North Pacific population which includes 14,000 to 18,000 fin whales and the southern hemisphere population which includes an upwards of 82,000 individuals. These populations reside in the North Pacific, Gulf of Mexico, California, Oregon, and Washington.

While their migratory patterns can change and are often difficult to chart, these ‘fintastic’ beauties make their way into the southern California area all throughout the year. Excited onlookers aboard our daily and year-round dolphin and whale watching safaris are often filled with glee when they spot one or many of these sleek and gentle giants. When spotted, they can be seen cruising at accelerated speeds, sometimes reaching 23 miles per hour. This zippy speed gives them their nickname of “the greyhound of the sea.”

Even though fairly shy and reserved when it comes to showing off their unique tail flukes and acrobatic breaching skills, fin whales are often very friendly with boats. As they make their way over to our whale watching vessels, passengers have been recipients of their friendly and curious stares, even checking out our fellow sea-faring friends in our underwater viewing pods.

Their curious glances and swift cruising habits bring absolute happiness to our day, and with the opportunity to spot them anytime throughout the year, we keep our flippers crossed for the next time they’ll say hello.

We hope you’ll join us soon as we make our way into their world to return their friendly hello’s.